THE CLASSIC HORROR FILM

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

Lesson 7 consists of eight video lectures and transcripts of those lectures, and five film excerpts. Start with excerpt #1 from Nosferatu and continue down the page in sequence until you reach the end of the lesson.

レッスン7は8本のビデオレクチャー(レクチャーのテキストがビデオレクチャーの下に記載されています)と5本の動画で構成されています。

このレッスンは、ページをスクロールダウンしながら最初から順番に動画を見たりテキストを読んでください。

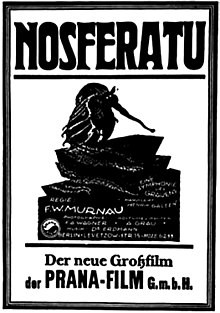

Directed by F.W. Murnau

Produced by Alban Grau

Written by: Henrik Galeen

Starring: Max Schreck, Gtustav Von Wangenheim and Greta Schroeder

Running time: 94 minutes

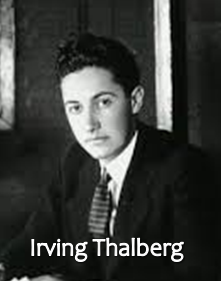

Part 1 – After the failure of The Man Who Laughs in 1928 Carl Laemmle made a bold decision. He remembered that the best business decision he ever made was to make the twenty-year-old Irving Thalberg his Head Of Production back in 1919, and the worst decision he ever made was to let Thalberg leave the studio after Thalberg produced incredibly successful The Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1923. Now, five years later and in desperate need of new ideas Laemmle appointed another twenty year old “boy genius” to be the Head of Production at Universal, his own son, Carl Laemmle Jr.. Eyes rolled when Carl Laemmle Jr. was given the place Irving Thalberg once had. This was because Carl Laemmle Sr. was famous, even legendary, for hiring members of his own family to work at the studio. At one time it was said there were fifty people with the name “Laemmle” working at Universal. The Poet Ogden Nash famously made a joke about Carl Laemmle’s hiring policies which went “Uncle Carl Laemmle / Has a very large family.”

People thought that Laemmle appointed his son Head of Production in the same way some fathers give their spoiled sons a sports car. They just could not believe that the boss’s son was anything like the unique genius that Irving Thalberg had been. They were right. It turned out that Carl Laemmle Jr. was a different kind of genius. Remember that Carl Laemmle Jr. was born in the year 1908 at almost the exact same time that the studios were moving to Hollywood. He quite literally grew up at the same time Hollywood did. He had been around movies and movie makers his entire life. In 1909, the year after he was born Hollywood was being created by studio executives, producers and directors who were men (99% were men) in their mid-twenties and early thirties. Hollywood was a young industry run by young men. As time went on and these young men became the bosses and they, in turn, continued to hire very young men to produce and direct the movies.

Even the top executives in the industry had an average age of only 45 throughout the 1920s. Carl Laemmle himself, one of the “grand old men” of Hollywood was himself only fifty-two when he made Irving Thalberg Head of production and Louis B. Mayer was only 39 when he became the head of M.G.M and hired Thalberg away from Laemmle. Irving Thalberg and “Junior” Laemmle were certainly the youngest of the many “boys” who ran Hollywood, but consider that Mark Zuckerberg was the same age they were when he started Facebook from his dormitory room at Harvard.

Boy geniuses: Irving Thalberg and Carl Laemmle Jr. were both 20 years old when they were made Head of Production at Universal in 1920 and 1928 respectively. They were two of the most powerful men (sic) in Hollywood. Today they would not be old enough to drink champagne to celebrate their success.

Like the tech industry of today, Hollywood in the 1920s was run by very young people. Pause for a moment and compare and contrast the corporate culture of Hollywood with corporate culture of Japan. What is the obvious difference? What are the advantages and disadvantages of these two different corporate cultures? Write your thoughts in your notes. You do not have to turn this assignment in. It is for you to keep in your notes for future reference.

Part 2 – Carl Laemmle Jr. was similar to Irving Thalberg in that he was willing to spend large sums of money to produce what he hoped would be hugely successful films. But he had a very different idea of what kind of movie he should spend money on. “Junior” was an early believer in the importance of sound movies and he especially embraced the new film genre we now call “the musical”. Just before the stock market crashed 1929 there was something of a miniature boom in making movies about Broadway musicals. Carl Laemmle Jr. committed Universal to a million dollar film entitled simply Broadway. It was yet another bitter disappointment. The film made only a very modest profit. This was especially frustrating because M.G.M. invested only $379,000 in their musical, Broadway Melody, which made an astounding $4,400,000. Ouch!

To add insult to injury, the much smaller Warner Bros studio released Gold Diggers of Broadway the same year at a cost of $532,000 and made $3,967,000.

This failure, combined with the crash of 1929, looked like the end for Universal Studios. But then Carl Laemmle Jr. remembered the huge success the studio had with The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera and he also carefully thought about what went wrong with The Man Who Laughs. Laemmle Jr. convinced his father to give “human tragedy” one more try. He convinced his father to buy the rights to Dracula.

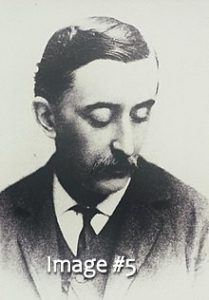

Bram Stoker

Part 3 – Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula 1897, was only a moderate success when it was published. What completely transformed the fortunes of the novel was the first (unauthorized) film adaptation of the story. This was the German film Nosferatu; A Symphony of Terror which we saw an excerpt from in our very first class.

The director of the film was the enormously talented young German director F.W. Murnau. Originally Murnau tried to buy the rights to the novel from Bram Stoker’s widow Florence Stoker-Balcombe, but perhaps because of anti-German feelings or perhaps because Germany was in an economic crisis in 1922 making the German currency almost worthless, Murnau was unable to purchase the rights. So, he simply changed the names of all the characters and the locations and called his film Nosferatu instead of Dracula. In other words, he stole the story. Florence Stoker-Balcombe sued Murnau for copyright infringement and eventually won her case in court. Murnau was ordered to pay her a settlement and the court ordered all copies of the film destroyed. The lawsuit actually drew attention to both the novel and the film. This new interest in the Dracula story led to the rights to the novel being sold to a playwright in 1924 and the play Dracula soon became a huge success first on the London stage and then on Broadway in America.

In fact, the play was revived in the 1970s and I remember going to see it when I was about twelve years old. It was wonderful.

Despite the court order that all copies of the film be destroyed, some copies of Nosferatu survived and we are today able to watch the film on DVD because of that. Let us once again see the scene we began our class with in lesson #1.

F.W. Murnau, uses the shadow of the vampire in a most terrifying way. (Image #1). Indeed, one of the more important aspects of German Expressionist style is the use of shadows. Murnau was a master of using shadows in his films. In Nosferatu, he is not content to just show us the already terrifying shadow of the vampire, he further distorted his shape in the grotesquely elongated shadow you see in Image #2.

Bizarre camera angles were also a very important aspect of German Expressionist style and when the vampire is traveling to Hutter’s city by ship, Murnau gives us an especially extreme camera angle.

The vampire looming over us (Image #3), can be contrasted with almost the opposite angle Murnau uses later when he shows us the vampire rising from inside of the ship, (Image #4) .

German Expressionist films are often considered the world’s earliest horror films and for good reason. These films grew out of the Germans’ reactions to the very real “horrors” of World War One. Not all German Expressionist films can be called horror films today, but most of them have a certain kind of story which the great Viennese psychologist, Sigmund Freud, called “unheimlich” in German. This word translates to the English word “uncanny”.

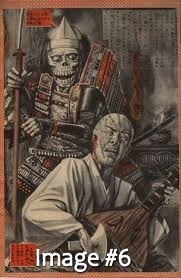

Japan has its own great tradition of “uncanny” stories which were collected by the writer Lafcadio Hearn (Koizumi Yakumo) 1850-1904 (Image #5) and published as “Kwaidan: Uncanny stories of Japan”. These are stories such as “Mimi Nashi Hoichi” and “Yuki Onna” (Images # 6 and #7)

German Expressionist films are usually about such “uncanny” stories. In addition to the strange camera angles and shadows the films used strange and often disturbing sets. In the film The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari all the sets were drawn in a completely artificial style with bizarre angles and sinister shadows throughout. Look at Images #8, #9 and #10.

However, F.W. Murnau took a very different approach to his sets when he made Nosferatu. He insisted on shooting his film on location at a real abandoned castle he found in Czechoslovakia.

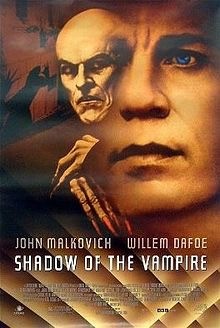

The making of Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) has become a story in itself, so much so that in the year 2000 film maker E. Elias Merhige made a film which he appropriately entitled Shadow of The Vampire. It is a fictionalized account of how Murnau made Nosferatu.

Directed by E. Elias Merhige

Produced by Nicolas Cate and Jeff Levine

Written by: Steven Katz

Starring: John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe

Running time: 92 minutes

Part 6

Shadow of the Vampire is no documentary film. It is a horror movie itself; a horror movie about the making of a horror movie. Murnau was obsessed with realism. He even went to the lengths of bringing his cast and crew all the way to Czechoslovakia to find a real castle that had the right feeling for the film.

(By the way, I went to Slovakia about three summers ago partly to see Orava Castle where Murnau made his film because sensei is sugoi horror movie no otaku). Orava castle is actually quite beautiful, but it is also…hmmm…unheimlich!

In Shadow of the Vampire, Merhige show us the lengths Murnau will go to in order to achieve realism in his film…almost any length!

Part 7 – We have finally met the strange actor named Max Schreck who plays the part of the vampire. Of course, I assume that you now understand Merhige’s joke; that the reason Max Schreck is able to play the part of a vampire so well is because he really is a vampire!

As the film progresses members of the crew and cast start to disappear and Murnau is aware the vampire is killing them. But Murnau is so determined to make his movie he is willing to make compromises with the vampire along the way. Merhige is being very clever showing us these moral failings in Murnau because it makes us wonder whether there is just one monster or two. The vampire is certainly a monster, but what about the man who wants to make a movie about a vampire so badly he hires a real vampire to be his star? Murnau really was a morally shaky character. He had, after all, stolen the story for his movie. Why not hire a real vampire?

The joke continues in this next except where the producer, Albin Grau, and the writer, Henrik Galeen, are getting drunk together when Max Schreck suddenly shows up.

Part 8 – The first point I would make about this scene is that something rather interesting we learn about the vampire is that he is a snob. He thinks Dracula is a sad novel because the vampire no longer has servants! This sounds like almost any wealthy person who has lost their money and social position complaining about their bad luck. But there is more going on here than just that and I will have quite a bit more to say on this subject in a future lecture. The second interesting thing we learn about the vampire is that when asked how he became a vampire he says “it was woman”! We can assume that he was once in love with this woman, but that something went wrong. Was he betrayed by her, was she taken away from him, what became of her? How did his relationship to a woman make him a vampire? The film never answers those questions. Merhige prefers to leave it as a mystery. But somehow love has played a part in this story just as it played a part in the stories of Quasimodo and Erik and Gwynplaine. But, while those characters were all somewhat tragic, Merhige makes his vampire a bit pathetic. He gets drunk and sad, but he can’t even really remember why he lost his love. That is quite a different vampire from the actual character of Count Orlock in Murnau’s film. As Galeen says, “Count Dracula wouldn’t say he can’t remember!” But the whole point of Merhige’s film is to go behind the original film and delve into the character of the fictional vampire as well as the very real director. Real or fiction? That is an interesting question for us, especially because the fictional character Bram Stoker created in his novel, Dracula, was based on a very real person in history. The reading home work for this lesson is about the real Dracula.