THE CLASSIC HORROR FILM

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

Lesson 24 consists of 8 video lectures and transcripts of those lectures, and 7 film excerpts. Start with the Video, Excerpt 1, and continue down the page in sequence until you reach the end of the lesson.

レッスン24は8本のビデオレクチャー(レクチャーのテキストがビデオレクチャーの下に記載されています)と7本の動画で構成されています。

このレッスンは、ページをスクロールダウンしながら最初から順番に動画を見たりテキストを読んでください。

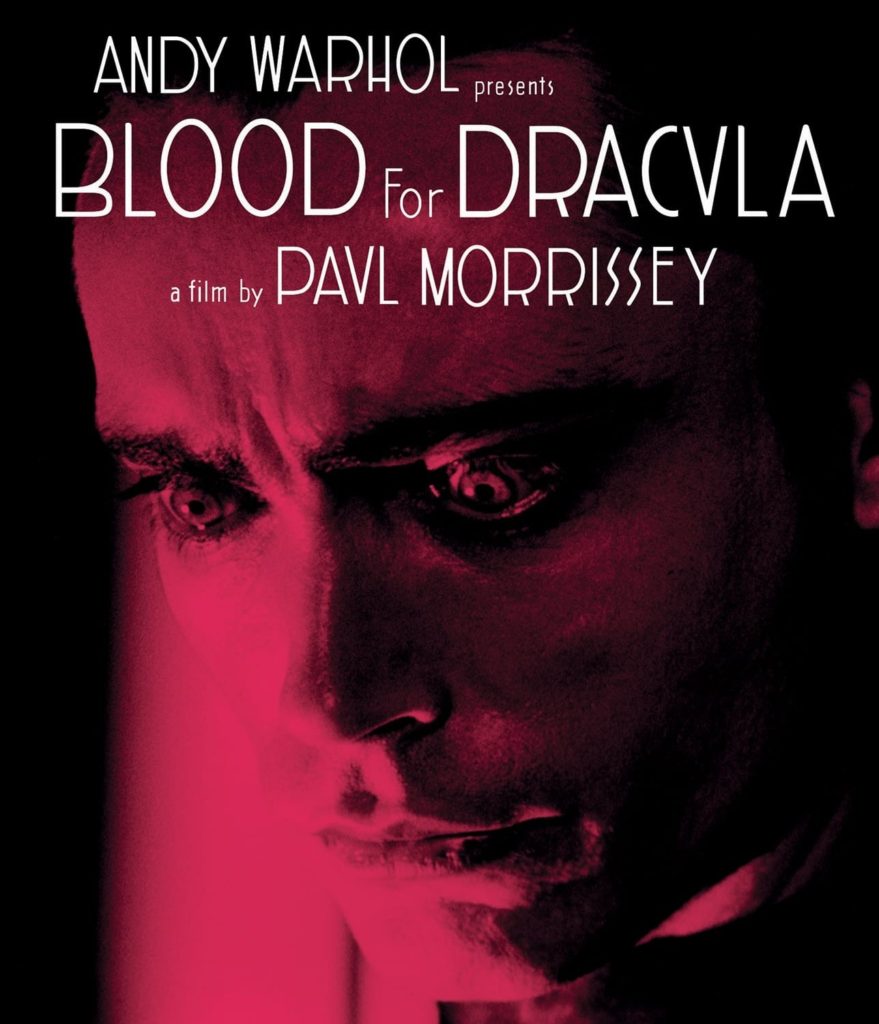

Directed by Paul Morrissey

Produced by Andy Warhol, Andrew Braunsberg, Carlo Ponti, Jean Yanne

Music composed by Claudio Gizzi

Screenplay by Paul Morrissey, Bram Stoker, Pat Hackett

Starring Udo Kier, Joe Dallesan, Vittorio De Sica, Arno Juerging, Maxime McKendry

Running Time: 106 minutes

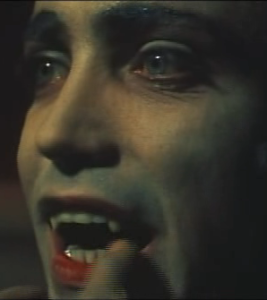

Part 1 – Paul Morrisey’s Blood for Dracula (1974) begins in a most interesting way. Udo Keir, the actor playing Dracula, is putting on makeup just as any actor would before his performance. This reminds us of the Vampire in Shadow of the Vampire who is pretending to be an actor playing the part of a vampire when in fact he is a real vampire pretending to be an actor. In Blood For Dracula, Dracula is making himself up to “play a part”. He will play the part of a younger, living man when, in fact, he is hundreds of years old. His white hair and deathly pale skin show his true age and his true state of decay. His family is also in the last stages of decay as we see in the next excerpt.

Part 1 – Paul Morrisey’s Blood for Dracula (1974) begins in a most interesting way. Udo Keir, the actor playing Dracula, is putting on makeup just as any actor would before his performance. This reminds us of the Vampire in Shadow of the Vampire who is pretending to be an actor playing the part of a vampire when in fact he is a real vampire pretending to be an actor. In Blood For Dracula, Dracula is making himself up to “play a part”. He will play the part of a younger, living man when, in fact, he is hundreds of years old. His white hair and deathly pale skin show his true age and his true state of decay. His family is also in the last stages of decay as we see in the next excerpt.

Part 2 – The Count, talking about his collection of dried flowers and stuffed birds, reminds us of Baron Frankenstein talking about the orange blossoms used at his family weddings; artificially preserved things that are frail and fall apart easily if they leave the ancient castles in which they are kept. Again, we are reminded of the extreme frailty of the nobility themselves and the system that sustains them. Unable to get the blood they need — in this case, the blood of virgins — the vampires of the house of Dracula are becoming more and more feeble until all they can do is lie in their coffins…not quite dead, of course, because they are, after all, the undead, but unable to move or speak. It is, as Dracula said in the 1931 movie, “worse than death”. It is as if they were like stuffed birds or dried flowers.

Part 3 – “Are your daughter’s virgins and are they available for marriage?” In other words, “Do you have girls for sale?”. As it so happens, the di Fiori family has four daughters, but the oldest is considered an “old maid” and the youngest still too young for marriage, but both the middle girls are “of marrying age” and their mother is eager to see them “married” (i.e., sold). The Marchesa believes marrying one of her daughters to this rich foreign Count will bring money back into her family. She is considering the marriage in much the way one would consider a business transaction. It wasn’t just the fathers who were complicit in arranging marriages like business transactions. Women who themselves had been given to their husbands in arranged marriages were very often party to arranging their daughters’ marriages in the same way. Just because people are victims of a system does not mean they don’t participate in victimization themselves.

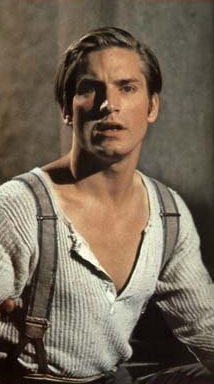

However, what the Marchese and Marchesa are unaware of is the fact that both their “eligible” daughters are no longer virgins since they have been regularly and enthusiastically having sex with the “handyman”, Mario. Mario, played by the legendary Joe Dellesandro, is an interesting young man with a lot to say for himself.

Part 4 – This was certainly a highly sexualized scene (and I am not showing you the steamiest parts, which were very steamy, indeed). It was all part of the film’s being about the “politics of sex”, or at least that is one interpretation that can be given of the film (other people think the film is just pornography). These aristocratic girls have no compunction whatsoever about having sex with the working class Mario, but obviously, neither sister would consider marrying him because he is not from the right “background”, not of their class. The relationship between Mario and the girls is purely sexual and somewhat abusive (on both sides). These people don’t even seem to like each other very much.

As we know, the film is set in approximately the year 1920, shortly after the Russian revolution and just before the fascist takeover of Italy; two revolutions on the opposite ends of the political spectrum, but both inspired by the flagrant ineptitude of the ruling classes in both countries. Mario gleefully recounts that in Russia the nobility lost everything (including their lives in many cases) and he looks forward to the downfall of the Italian nobility warning the girls they won’t even have their “crummy house” after the revolution. Perhaps it is ironic that while Mario is telling them about the dangers of revolution, the di Fiori daughters seem oblivious to the far more immediate danger they face from Dracula, a member of their own “class” who plans to murder them in order to drink their blood. The girls are too busy planning shopping trips to Paris to worry about such things as vampires. They will pay a terrible price for their ignorance and selfishness. As part of their selfish plan, they want to keep Mario as a kind of toyboy or “slave” after one of them marries Dracula. But, Mario, as we shall see, has other ideas and he certainly has no intention of being anyone’s “slave”.

As we know, the film is set in approximately the year 1920, shortly after the Russian revolution and just before the fascist takeover of Italy; two revolutions on the opposite ends of the political spectrum, but both inspired by the flagrant ineptitude of the ruling classes in both countries. Mario gleefully recounts that in Russia the nobility lost everything (including their lives in many cases) and he looks forward to the downfall of the Italian nobility warning the girls they won’t even have their “crummy house” after the revolution. Perhaps it is ironic that while Mario is telling them about the dangers of revolution, the di Fiori daughters seem oblivious to the far more immediate danger they face from Dracula, a member of their own “class” who plans to murder them in order to drink their blood. The girls are too busy planning shopping trips to Paris to worry about such things as vampires. They will pay a terrible price for their ignorance and selfishness. As part of their selfish plan, they want to keep Mario as a kind of toyboy or “slave” after one of them marries Dracula. But, Mario, as we shall see, has other ideas and he certainly has no intention of being anyone’s “slave”.

Part 5 – Mario is nobody’s servant any more than he is anyone’s slave! As he explains to the Counts’ secretary, Anton, he is a “worker”. That was a crucial distinction. The word “servant” comes from Latin, where it actually has the meaning “slave’’. This meaning is found in such words as: deserve, disservice, servant, serve, service, servile, servitude, subservient. On the other hand, “Worker” means “one employed for a wage”, i.e., someone who sells their labor for an agreed-upon price.

Part 5 – Mario is nobody’s servant any more than he is anyone’s slave! As he explains to the Counts’ secretary, Anton, he is a “worker”. That was a crucial distinction. The word “servant” comes from Latin, where it actually has the meaning “slave’’. This meaning is found in such words as: deserve, disservice, servant, serve, service, servile, servitude, subservient. On the other hand, “Worker” means “one employed for a wage”, i.e., someone who sells their labor for an agreed-upon price.

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth, “workers” such as Mario were becoming increasingly conscious of the “class system”, a system with its origins in the feudal system in which the nobility ruled over the peasants as masters rule over slaves. Mario is more than just a “worker”, though. He has educated himself about the class system and believes that the workers should be “on top” and those who are not workers should be “on the bottom”. He expresses these ideas when he and the count have a conversation.

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth, “workers” such as Mario were becoming increasingly conscious of the “class system”, a system with its origins in the feudal system in which the nobility ruled over the peasants as masters rule over slaves. Mario is more than just a “worker”, though. He has educated himself about the class system and believes that the workers should be “on top” and those who are not workers should be “on the bottom”. He expresses these ideas when he and the count have a conversation.

Part 6 – The contrast between Mario, the worker, and Dracula, the nobleman, could not be more stark. Dracula is so feeble he needs a wheelchair and can barely get up the stairs by himself, while Mario is the picture of good health and strength. Mario asks, “Do you want me to carry you?” Servants (peasants) had been “carrying” the enfeebled nobility for centuries of course. Mario tells the count “nobody believes in that class stuff anymore, it’s a thing of the past”. But the Count scornfully accuses Mario of dreaming. Mario counters by saying he “reads books, too” and he knows “how things should be”.To put it mildly, Mario is a Marxist, (apparently a well-read one) and to be honest the film is far more a Marxist film than it is a feminist one.

Part 6 – The contrast between Mario, the worker, and Dracula, the nobleman, could not be more stark. Dracula is so feeble he needs a wheelchair and can barely get up the stairs by himself, while Mario is the picture of good health and strength. Mario asks, “Do you want me to carry you?” Servants (peasants) had been “carrying” the enfeebled nobility for centuries of course. Mario tells the count “nobody believes in that class stuff anymore, it’s a thing of the past”. But the Count scornfully accuses Mario of dreaming. Mario counters by saying he “reads books, too” and he knows “how things should be”.To put it mildly, Mario is a Marxist, (apparently a well-read one) and to be honest the film is far more a Marxist film than it is a feminist one.

The Russian Revolution, which Mario has mentioned before, was a Marxist revolution in which the “worker” was elevated from the lowest rank in society to the highest. In fact, the revolution divided society in two with “workers” deserving respect for their labor as opposed to “parasites” who did not work but lived off the labor of the workers. “Worker” could mean peasant, factory worker, soldier, policeman, student, teacher, scientist, engineer…even actors, musicians, and artists. But, nobles were all “parasites”. The word “parasite” means “an organism that lives in or on another organism of different species (its host) and benefits by deriving nutrients at the host’s expense”. In other words, Marxists considered nobles to be “parasites”, creatures that “feed off of humans”, but who are not themselves human, something like…a vampire?

WARNING: THE NEXT EXCERPT IS VERY VIOLENT AND BLOODY

(BUT VERY FAKE LOOKING).

IF YOU DON’T WANT TO WATCH IT, YOU DON’T HAVE TO. READING ABOUT IT WOULD BE SUFFICIENT.

Part 7 – In our films, we are used to Dracula and other vampires with supernatural strength and abilities, but as Mario chases Dracula, we realize this vampire has none of that. Confronted by the strength of this young worker, the vampire is helpless. Mario chops off both his arms and both his legs, leaving Dracula to squirm on the ground like a parasite (parasites are often worms) still protesting “I’m not like you!”.

Dracula had only succeeded in turning the oldest daughter, Esmerelda, into a vampire like himself (because as an “old maid” she was still a virgin). She begs Mario to let them go, but like the good revolutionaries of Russia, Mario has no intention of letting this “parasite” escape. Explaining, “He lives off of other people, he’s no good for anything and he never was”…he drives the wooden stake into Dracula’s heart destroying him.

Paul Morrisey took the Horror film to its logical extreme, its logical conclusion. The films were always subversive, always suggesting and hinting that the conflict was about class. Morrisey just made his horror film an openly Marxist revolutionary one.

Part 8: In Conclusion

Let us conclude by recalling some of what you learned this year. We learned what horror is: it is more than just being scared, it is feeling…well, exactly as I described how Christians feel watching Dracula corrupt their most sacred ceremony or how they feel watching Frankenstein create a new life from the parts of dead men. You might not be a Christian, but you have learned enough about what Christians believe to understand how they must feel watching these scenes. I know you can understand how they feel, because I am not a Christian either, and yet I understand how they must feel.

We also learned that human beings seem to have a deep psychological need to see that which horrifies them, to confront it somehow. We may want to cover our eyes and hide from these things, but our curiosity and need to see often gets the better of us. We want to peek from under the covers and see that which horrifies us. The things that horrify us the most are not just acts of bloodshed and violence, they are things that are truly forbidden, that are taboo. These are sometimes culture-specific as when Dracula mocks the Eucharist or when Frankenstein creates life, but sometimes they are universal. At the end of The Wolf Man, when Lord Talbot is at last exhausted from beating the monster to death with the cane and looks at what he has done and sees that he has killed his own son, everyone can identify with his feeling of horror! The horror and tragedy of Larry Talbot’s end is magnified by the fact he became a monster against his own will. Larry never wanted to be a monster.

Did Erich, the phantom of the opera, want to be a monster? Erich told Christine he was a monster because that is what men made him become. The same was true for Quasimodo. It was how these ugly men were treated by others that made them monsters. Ah, but Erich chose to be evil and Quasimodo chose to be good! Yes, we also learned that evil is about making choices. We are only innocent when we are children because we do not know the difference between good and evil when we are children. But after we have eaten the fruit of knowledge, we know what evil is and we know we should not steal, rape, and kill. Yet we watched the monster in Frankenstein kill not once, but three times. However, in all three cases, we judged the monster to be innocent of the crime of murder because he either killed in self-defense or by accident. We learned to appreciate the fact that good and evil are not always black and white, that there are nuances and exceptions to be considered.

For example, we learned that even a man “pure of heart may become a werewolf when the wolfsbane blooms”. Leon Corrido did not want to become a werewolf and kill any more than Larry Talbot. When Leon wakes up the next morning after he has killed Jose and the prostitute and sees the blood on his hands he screams and cries in horror. As we consider the nuances and exceptions I mentioned just now, we have to acknowledge that not only do people sometimes kill in self-defense or by accident but sometimes they may do so because they have lost their minds and have no control over themselves. You can only be held responsible for what you know is wrong. A werewolf has no sense of right or wrong, good or evil.

But, not all monsters are innocent of course! We acknowledge the evil of men like Dracula or the Marquis di Siniestro, but we also remember that Hollywood horror films showed us that these monsters were enabled by the feudal system itself which was institutionally evil. In other words, Count Dracula, Countess Bathory, Henry Frankenstein, or the Marquis di Siniestro are not just evil men and women, they are part of an evil system that gives them the power to harm others.

It is this last idea that was so unique to horror films and that made them special and different from other types of films because the idea is so subversive. If something is “subversive” it seeks to undermine an established system or institution. Horror films subvert the very systems and institutions the Production Code Administration was designed to protect and uphold: church, government, the class system.

How are horror films subversive? Consider again the example I used of a man going through a woman’s bedroom window and approaching her with an evil look on his face. The PCA would never have allowed such a scene in a normal movie, but because Dracula is a vampire he is allowed to do this. Now use that same logic and apply it to some of the other scenes in our horror films. If you are chained up in prison and you kill the man who tortures you with fire and a whip how are you judged at the end of the film? Are you evil or innocent? In the film, you die like Jesus Christ, on a hill with a mob of angry people killing you because they do not understand that you are innocent. That is subversive.

Showing us that the real evil monsters are not the “freaks” in the circus, but instead, the normal looking people who torment them is subversive. The film Freaks made audiences uncomfortable because it showed them that they could actually be the monsters.

The Bride of Frankenstein as a “camp” movie with a “gay sensibility” and the implied lesbianism in Dracula’s Daughter were both subversive films because to even hint at the existence of any sexuality that the Church did not accept as “normal” was to challenge the invisibility of LGBTQ people …and when we are visible it is harder to mistreat us, abuse us and dismiss our rights. That is subversive.

But surely, I am not suggesting that these films are actually on the side of the so-called “underdog” the monsters? After all, don’t the monsters almost always end up dead at the end with the normal people going off to get married and start a nice normal family? Consider how we get to these “happy endings”. Whose story was it we were watching anyway? If you want the answer to that just go through the titles of our films: Nosferatu, Phantom of the Opera, The Man Who Laughs, Dracula, Freaks, The Wolf Man. In each case, the monster or monsters are the ones we watch in the film, the ones we learn about. Of course, there is the notable exception of the greatest film of them all, Frankenstein. This film is not named after the nameless monster but instead is named after the man who created him. But from the moment the monster walks through the door and shows us his face, he becomes the focus of the film and it becomes his story, not Henry Frankenstein’s. In the sequels that followed after The Bride of Frankenstein, the monster does get a name! He is actually called “Frankenstein” in the promotions for the films from 1939 on. In other words, the monster not only stole the movie from Henry Frankenstein, he eventually ends up stealing Frankenstein’s name as well. The illegitimate child takes his father’s name.

In fact, even making movies with ugly or evil monsters as the “stars” was subversive. This is why Joseph Breen and the Church and the PCA and the new management at Universal tried so hard to kill the horror film in the mid-1930s because it was subversive. But they couldn’t make it stay dead. The horror film, like Dracula, came back from the dead not just once but several times with sequels and series and reboots that continue to this day. Horror films are never going away because we still need them.

I hope that through these films you had a chance to learn about all the things I mentioned above, but most of all, I hope these films gave you a chance to learn a bit about yourselves and what you think about all these things. If you know what you think about some of these issues, if you know yourself a little bit better after this class, I would say that you have and I have done our jobs well.

Thanks for watching!